First, if you like what you see in today’s blog, you are bound to like how I will be teaching this approach to AI-based neural networks and Design of Experiments in my upcoming (May, 2026) Insect Rearing Fundamentals class.

I have been touting the advantages of using design of experiments (DoE) to help us better understand interactions of components in insect rearing systems and to further our grasp of which components are potent forces towards the improvement of our systems. In this blog entry, I am trying to explain how we might start some initial rearing system inquiry using the powerful AI tool neural networks (often called artificial neural networks). I use the JMP statistical package for my DoE and other statistical practices, and I have found the JMP procedures to be very user friendly for people like me who are NOT mathematicians or statisticians. This is especially the case for my learning to apply neural network processes to my rearing inquiries.

For one thing, in my many ventures into websites and other resources that help explain the nature, value and procedures in neural networks, I found a most compelling, entertaining, and clear tutorial from Professor Dmitry Shaltayev (https://youtu.be/u-ngF1YXqhY ). Though his presentation does not use examples from insect rearing, he is very clear and very compelling in his tutorial. First, he starts with the derivation of neural networks from the mammalian nervous system where neurons have dendrites, cell bodies, and axons that receive and process neurological information. He further explains how neural networking/AI is central to facial recognition, self-driving cars, and many other applications. He also uses the JMP software, so his explanations are very useful to me in my JMP neural network adventures.

Secondly, I must mention (by way of a plug for my book: Design, Operation, and Control of Insect Rearing Systems, Cohen. 2021. CRC Press. Boca Raton FL) that I have already made an argument for using neural networks, and my examples here are taken from my discussion.

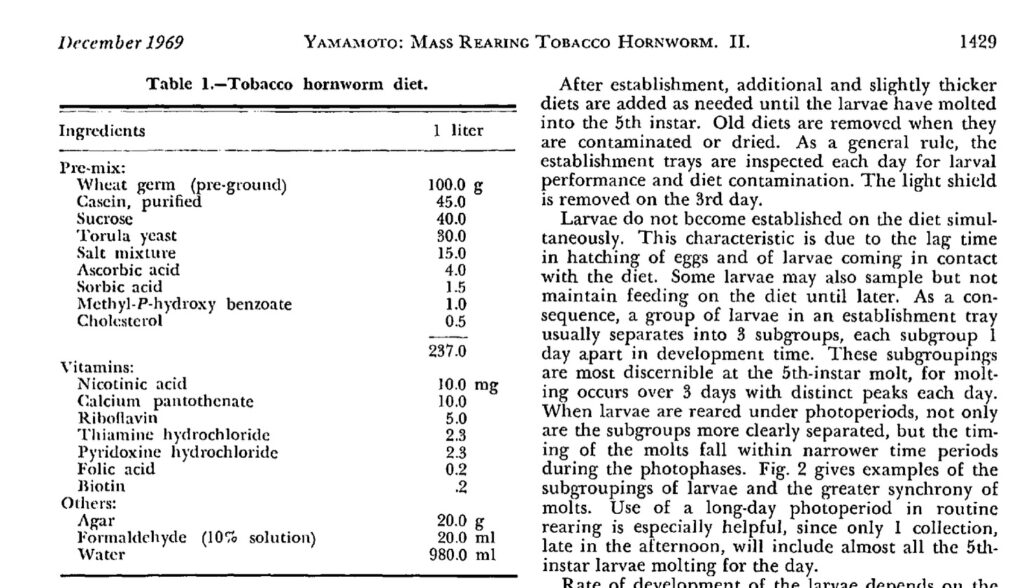

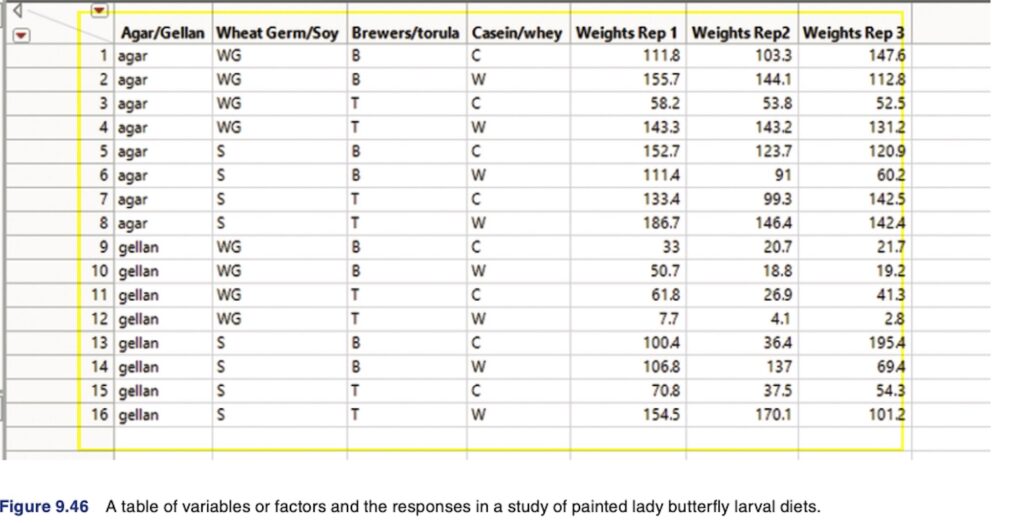

In this study, I had used design of experiments to set up an experiment with diets for painted lady butterflies, using their weights as the responses and several diet components as the factors (or experimental variables). Here is the data table representing these values:

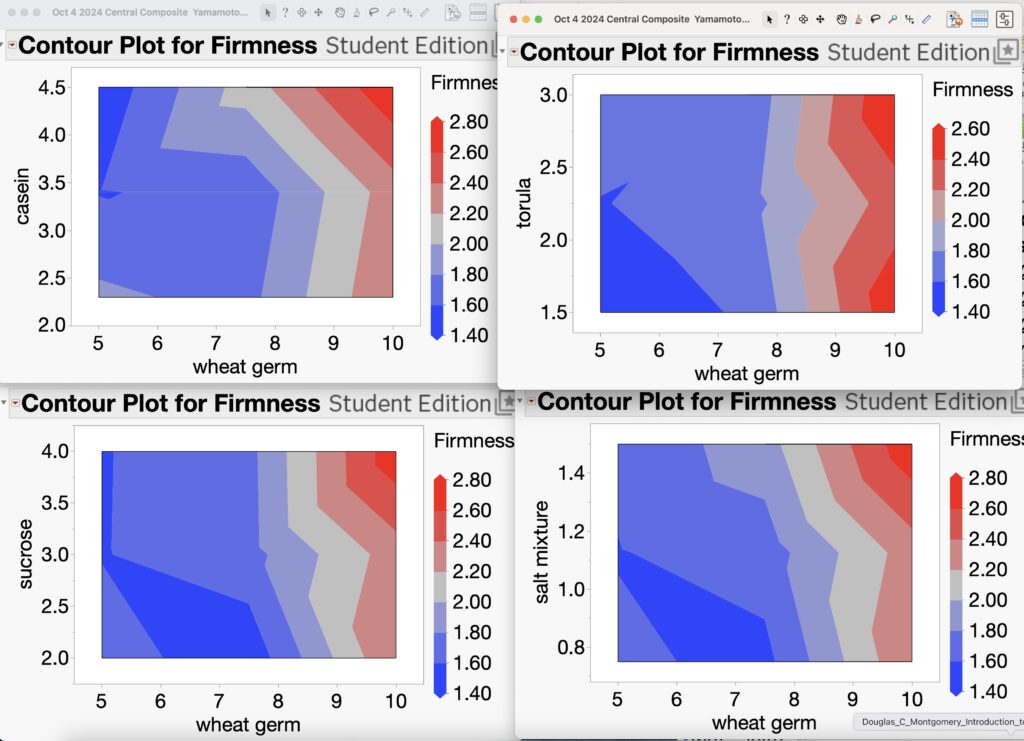

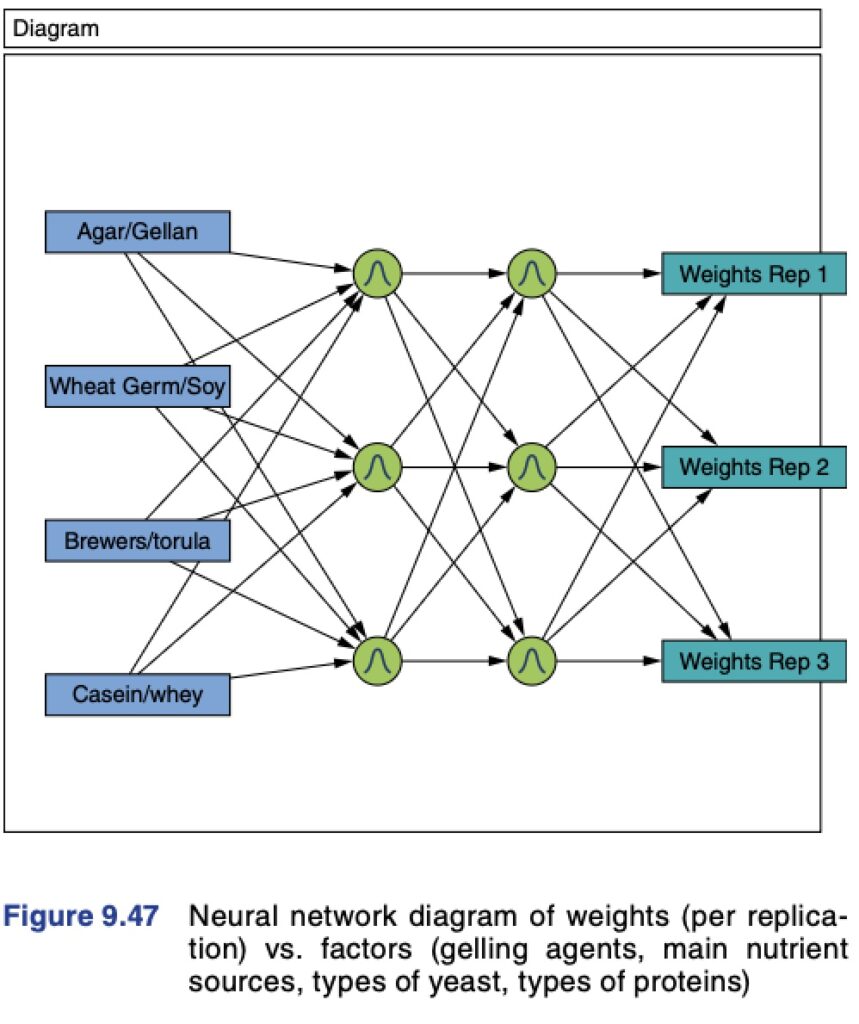

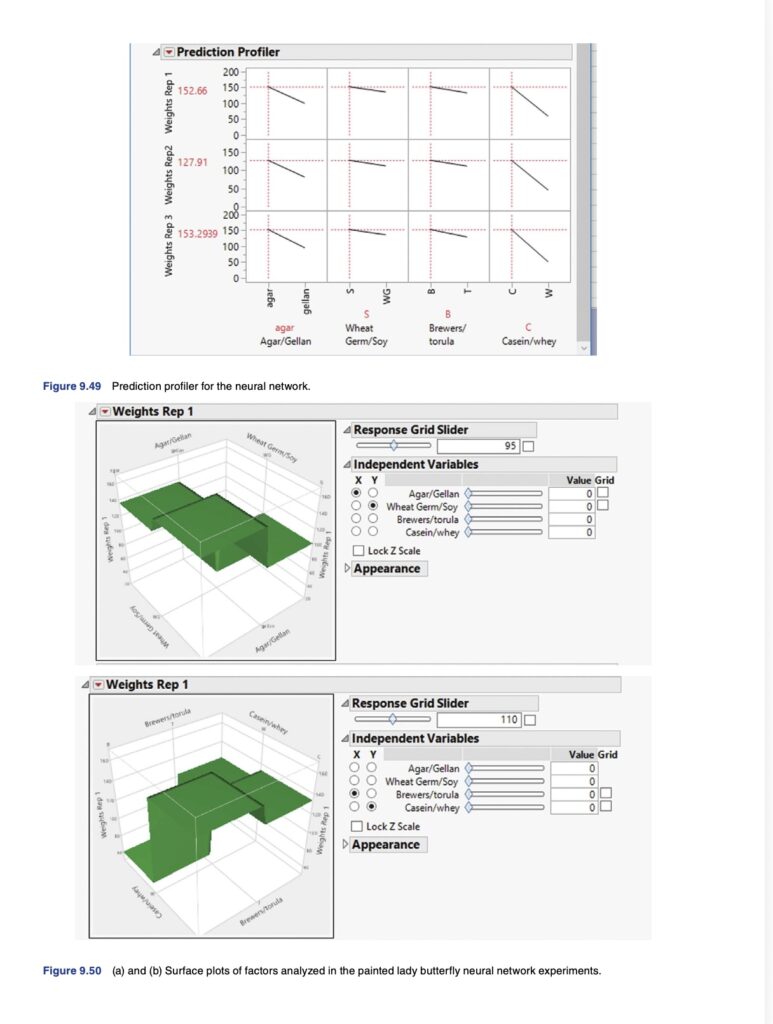

Next I fed the terms (factors and responses) into a JMP neural network analysis and got this diagram to represent the inquiry;

First, please note the Prediction Profiler (a typical output of JMP analyses) and the little graphs that show, for example, that between agar and gellan as gelling agents, agar use consistently resulted in greater biomass. Also, soy flour showed a slight but consistent tendency to yield higher body weights than wheat germ; brewer’s yeast here seemed slightly better than torula yeast, and casein gave much better results (higher weights) than did whey protein.

Second, I point out that this system of running multiple factors (rather than one factor at a time) is much more useful in understanding interactions of the components and giving us a much more realistic experimental framework where the factors are “dissected out” to show their contributions to the responses.

Third, I caution the readers that this set of experiments is still not definitive. The outcomes may vary according to which species are being explored, which sources of the components are being used (agar varieties differ from supplier to supplier and even from batch to batch).

I will address all this and more in near future blogs. I hope you tune in, and I hope you are encouraged to think about using DoE and neural networks to develop and improve your rearing systems!

Happy Rearing!