I have been teaching insect rearing on a regular basis for the past 20 years, and I actually taught my first course in insect rearing (at the University of Arizona) in 1981 and again in 1989. Over all these years of teaching, I have taught workshops (initially at Mississippi State University, then in Tucson, and most recently here at North Carolina State University). I have also taught a number of in person courses as well as several online (both synchronous and non-synchronous), and I have taught both for college credit and not-for-credit courses. I point this out to convey the idea that I have considerable experience with several forms of rearing education; I have given it considerable thought I have devoted to insect rearing education over the past 40 years; and I feel that I have some constructive perspectives about how rearing education can become a highly useful investment of resources.

Workshops vs. Courses: I use the term “workshop” to mean a compressed teaching/learning effort in a subject such as rearing. I see workshops as lasting from 1 or 2 days to 5 days, with each day being devoted to intense or concentrated lecture, demonstration, and discussion. To my knowledge, the insect rearing workshops have been 5 days long, with about 8 hours per day dedicated mainly to lectures on topics such as diets, facilities, environment, genetics, quality control, microbial relations, and safety, with some variation of these topics such as special attention to air handling systems. Again, to my knowledge, rearing workshops include tours of onsite rearing facilities to give participants direct observation experiences. Workshops generally are taught by several experts in various topics of insect rearing, and the experts’ presentations are coordinated by an organizer. One very popular aspect of workshops is that the participants travel to the site of presentations, getting to meet other participants and instructors and experiencing luncheons, banquets, visits to local attractions. The meeting opportunities are during meals, at breaks, and in evenings between workshop days. I have heard testimony from participants that the meeting with fellow rearing professionals was an extremely valuable aspect of the workshop experience.

Downsides of the workshop format are that participants must devote at least 6 days to attend and travel to and from the workshop site; besides the time investment, there is a considerable financial investment including workshop fees, travel and per diem expenses. In the time of COVID-19, the risks and hardships of travel are prohibitive for many people. Pedagogical Downsides include the pace of information processing—learning is not efficient when too much new information is processed within a short period of time. Besides the rapid pace of information transfer, workshops are limited in opportunities for interaction between participants and instructors.

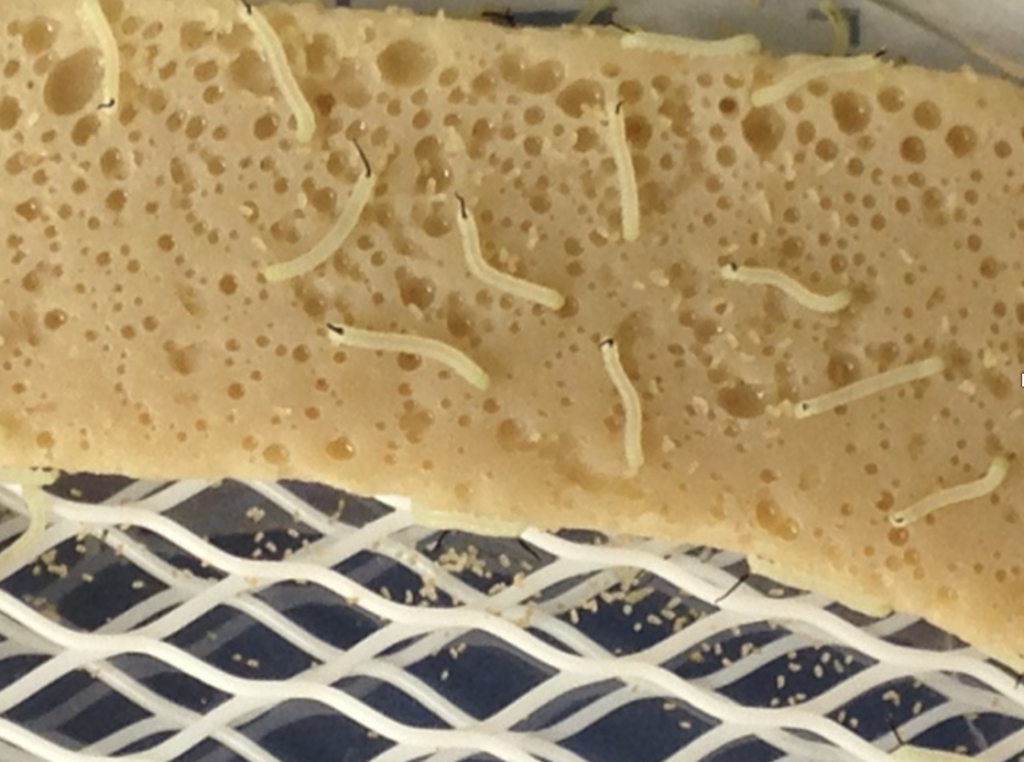

These thoughts about workshop limitations motivated me to offer courses in insect rearing for the past decade. In 2010, I offered a graduate seminar in insect rearing at North Carolina State University. The course was one hour a week for fifteen weeks, and most of the presentations were given by students on topics they selected. I felt that the seminar format lacked the scope and depth that was needed to convey the broad concepts and granular details of insect rearing. Therefore, in 2011, I offered the first 3-unit course in insect rearing where I lectured for 3 hours per week (for 15 weeks), and the students did projects where they reared insects of their choice and incorporated the materials taught in class. Students, working in groups of three, reared several species of insects that they were working with for their graduate studies or insects that lent themselves to gaining rearing experience (thrips, cockroaches, hornworms, lacewings, stink bugs, etc.), and they applied methods such as lipid, protein, and carbohydrate analysis, diet texture analysis, microscopic imaging studies, and other techniques that they could explore in my lab or in other facilities available at NCSU.

In the first (2011) class, there was no testing; grading was based on presentations as 1) posters, 2) PowerPoints, and 3) written papers in conventional scientific format. Despite the considerable time students spent with their team-based projects, I felt that learning was not as effective as possible due to the lack of testing. In subsequent offerings of the onsite rearing courses (in 2013, 2015, 2017, and 2019), I added two mid-term and one final exam, which consisted of take home, open-book essay questions. Because of the value of hands-on work, I retained the projects as part of the course requirements, and I offered opportunities for students to visit labs where they could learn about texture analysis (food rheology) and various analytical procedures in my lab. Student evaluations of these courses were very positive with many students writing that these courses were some of the best classes that they had taken and that every entomology student should take such a rearing course. Students, generally responded well to the course motto: “Know your insect.” Most students also got the point about the need to view insect rearing as a science, rather than an art.As a long-time educator, I was generally pleased with the onsite classes in insect rearing, but I was concerned that I was not able to reach the thousands of people who need and desire more opportunity to understand insect rearing in North America and world-wide. Therefore, I developed an online, non-synchronous course in rearing science and technology. I will make another post (soon to follow this one) on the further development of online courses.

![http://www.csrtimys.res.in/structure/seri-engineering-division Central Sericultural Research & Training Institute (CSRTI), Mysore [An ISO 9001 : 2008 Organisation] CENTRAL SILK BOARD - MINISTRY OF TEXTILES - GOVT. OF INDIA](https://www.werearinsects.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/high-efficiency-mulberry-farming-in-India-300x201.jpg)