In the previous post (Nov. 26), I brought up the subject of insect rearing infrastructure, and I showed a sterling example of a rearing system that has served the world well: the Pink Bollworm Rearing System: run by the USDA, APHIS in Phoenix, AZ (USA). I showed a picture of the “pinkie” diet that was being mass-produced in a huge, industrial scale twin screw extruder. Although the process is now practiced routinely by the highly skilled professionals at the Pinkie facility, the ideas and techniques behind this smooth operation did not “like Athena spring full-blown from the head of Zeus.” There was an evolution of the process that serves today to produce up to 25,000,000 pinkie adults per day for sterile release.

So here is the pink bollworm system running at very high efficiency. But how did it get that way? What incremental steps went into the rearing system: the diet, the environmental conditions, the containers, the sanitation procedures, the genetic management of a highly domesticated insect, etc.?

So here is the pink bollworm system running at very high efficiency. But how did it get that way? What incremental steps went into the rearing system: the diet, the environmental conditions, the containers, the sanitation procedures, the genetic management of a highly domesticated insect, etc.?

Let’s take the diet as an example of the evolution of a mass-rearing system. The above table is from a paper by Edwards et al. (1996) cited below. The Edwards paper describes how the twin screw extruder became incorporated into the mass-rearing system (another huge and important series of steps), but the formulation of the diet itself came from a complex of incremental processes, all of which had to be vetted. Looking at the components, we see for example toasted soy flour, wheat germ, and agar. Each of these components has a special role in the diet, nutrition, feeding stimulation, antimicrobial function, texture, stabilization, etc. But where did the idea of soy flour come from? It turns out that tracking soy flour (and other soy products) in insect diets requires some complex detective work (which I will discuss in another post). However, it appears that soy products were first used by Japanese researchers who were trying to develop artificial diets for silkworms to reduce dependence on fresh mulberry leaves (please see my other posts on silkworms). The soy/ silkworm papers began to appear in the early 1960s, and later in the ’60s other papers appeared where soy components were reported by Western researchers on insect diets. I will treat the background in soy in insect diets in another post dedicated to this special topic.

Let’s take the diet as an example of the evolution of a mass-rearing system. The above table is from a paper by Edwards et al. (1996) cited below. The Edwards paper describes how the twin screw extruder became incorporated into the mass-rearing system (another huge and important series of steps), but the formulation of the diet itself came from a complex of incremental processes, all of which had to be vetted. Looking at the components, we see for example toasted soy flour, wheat germ, and agar. Each of these components has a special role in the diet, nutrition, feeding stimulation, antimicrobial function, texture, stabilization, etc. But where did the idea of soy flour come from? It turns out that tracking soy flour (and other soy products) in insect diets requires some complex detective work (which I will discuss in another post). However, it appears that soy products were first used by Japanese researchers who were trying to develop artificial diets for silkworms to reduce dependence on fresh mulberry leaves (please see my other posts on silkworms). The soy/ silkworm papers began to appear in the early 1960s, and later in the ’60s other papers appeared where soy components were reported by Western researchers on insect diets. I will treat the background in soy in insect diets in another post dedicated to this special topic.

Wheat germ is another component that is prominent in the pinkie diet and in diets for hundreds of other insect species. I have treated the history of wheat germ in my text, especially in the 2nd edition, and I will discuss it on a special topics page in a later blog, but for now let me point out that wheat germ made an inauspicious debut in 1959 and then a much greater impact study reported in 1960 (please see Vanderzant et al. 1959 and Adkisson 1960) . Once the vast potential of wheat germ became recognized it has been of central importance in thousands of published studies where the insects could not have been available were it not for the excellence of what germ as a diet component.

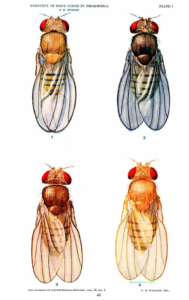

The last item that I will mention here is agar. It seems that agar has been around forever in insect diets, but it actually became a centerpiece of insect diets starting with a Drosophila paper by Baumberger (1917) and Baumberger and Glaser 1917. Prior to 1917, media were being developed for Drosophila based on bananas and yeast, but the Baumberger laboratory borrowed from the then burgeoning programs in microbiology where agar was becoming a standard of many kinds of microbial media. The advent of agar in insect diets revolutionized the potential for rearing hundreds of species of insects, yet the Baumberger and Baumberger and Glaser papers are cited only a total of 2 times since 1917! This lack of citation and lack of recognition of some of the most influential achievements in insect rearing is a central topic of many of my writings and teachings.

Finally, the story of many of the other innovations and advancements is told remarkably well by Stewart (1984). Again, I will treat the pinkie story in more detail in near future pages, but for now please understand my point about how much incremental progress must take place and should be recognized in the insect rearing systems upon which so much depends!

References Cited Here:

Adkisson, P. L., E. S. Vanderzant, D. L. Bull, and W. E. Allison. 1960b. A wheat germ medium for rearing the pink bollworm. J. Econ. Entomol. 53: 759-762.

Baumberger, J.P. 1917. Solid media for rearing Drosophila. American Naturalist. 51: 447-448.

Baumberger, J.P. and R. W. Glaser. 1917. The Rearing of Drosophila Ampelophila Loew on Solid Media. Science. 45: pp. 21-22.

Edwards, R. H., E. Miller, R. Becker, A. P. Mossman, and D. W. Irving. 1996. Twin screw extrusion processing of diet for mass rearing the pink bollworm. Transactions of the American Society of Agricultural Engineering. 39 (5): 1789-1797.

Stewart, F. D. 1984. Mass Rearing the Pink Bollworm, Pectinophora gossypiella. In Advances and Challenges in Insect Rearing. E.G. King and N.C. Leppla, Eds. USDA, ARS. Pp. 176-187. New Orleans, LA.

Vanderzant, E. S., C. D. Richardson, and T. B. Davich. 1959. Feeding and Oviposition by the Boll Weevil on Artificial Diets. J. Econ. Entomol. 52: 1138-1142.