Insect rearing is a process. The desired outcomes in rearing are to have insects that are healthy, representative of their species, readily available, useful for various programs (research, crop protection, conservation, as food for other organisms, etc.) Being a process, insect rearing can be made more useful by application of process control, specifically statistical process control (SPC). This concept was realized by a few pioneering authorities in insect mass rearing (including Boller et al. 1981 and Calkins et al. 1994: it should be noted that D. Chambers , T. Ashley, and E. F. Boller were suggesting the application of statistical quality control and SPC back in the 1970s, and a few facilities had adopted their suggestions.)

R. T. Staten and A. C. Cohen checking for problems in USDA, APHIS colony of big-eyed bugs in mass-rearing facility for predators

Getting Started in SPC:

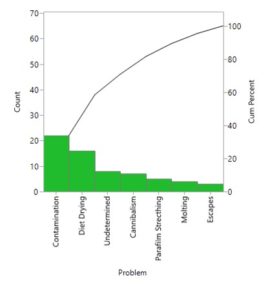

A good first move in developing a process control system is to determine WHAT we are trying to control or what the problems may be = the causes of error or variability that have crept into our system. A nearly universal tool or model of decision-making about which processes contribute the most to the benefit or the harm of our system is the Pareto analysis. So, for example, when we were trying to mass rear predators such as big-eyed bugs (upper left figure with R. T. Staten and A. C. Cohen in the Phoenix USDA, APHIS lab in 1995 or the lacewing rearing as in the upper right image), we would try to reduce mortality in our system. With careful observation by the rearing specialists, we decided that in one rearing unit (one rack) in our system we had the following causes of mortality or loss:

In this case, we found that 22 deaths could be attributed to mold in the diet, 16 deaths from diet drying out, and cannibalism, poor stretching of the Parafilm membrane preventing the proper feeding seen in the upper right diagram, problems with molting, and escapes accounting for other loses. In 8 containers, the causes of failure were not determined, possibly unseen pathogens or genetic defects.

The point here is that once we had collected data on the most likely causes of loss and the relative frequency of these causes, we could launch an effort to correct the problems, and clearly dealing with contaminants would be the most fruitful in improving our rearing outcomes (since nearly half the loses came from contamination. This data-driven conclusion was based on the Pareto analysis, which is a simple tool that helps to shape decision-making about rearing system improvements.

This simple example tells us these things (take home messages): 1) collecting data is where to start, 2) using the expertise that is available is helpful in deciding what data to collect and how to interpret (e.g. how do we know how to recognize mold or desiccated insects?), 3) analysis of the data with graphic techniques can be very useful.

In a soon to be posted blog, we will cover some approaches taken to improve the problem with straggling in the Forest Service gypsy moth colony at Hamden, CT back in the late 1980’s (see ODell 1992 below). It’s an excellent example of problem-solving approaches.

Boller, E. F., B. I. Katsoyannos, U. Remund, and D. L. Chambers. 1981. Measuring, monitoring, and improving the quality of mass-reared Mediterranean fruit flies, Ceratitis capitata Wied. 1. The RAPID quality control system for early warning. Z. angew. Entomol. 92: 67-83.

Calkins, C. O., K. Bloem, S. Bloem, and D. L. Chambers. 1994. Advances in measuring quality and assuring good field performance in mass reared fruit flies. Pp. 85-96. In C. O. Calkins, w. Klassen, P. Liedo [eds.], Fruit flies and the sterile insect technique. CRC Press. Boca Raton, Florida. U.S.A.

ODell, T. M. 1992. Straggling in gypsy moth production strains: a problem analysis for developing research priorities, pp. 325-350. In T. A. Anderson and N. C. Leppla [eds.], Advances in insect rearing for research and pest management. Westview, Boulder, CO.